How consumer companies can drive growth at scale with disruptive innovation

I n the era of “fast products” and digital disruption, delivering growth requires putting in place new predictive consumer-growth capabilities, including innovation, based on speed, agility, and scale. Innovation is central to the mission, values, and agenda of most consumer-packaged-goods (CPG) companies. However, in the last several years, incumbent CPGs have struggled to keep pace with start-ups, which have reinvigorated and reinvented categories ranging from ice cream to diapers.

By Mark Dziersk , Stacey Haas , Jon McClain, and Brian Quinn

Innovation is central to the mission, values, and agenda of most consumer-packaged-goods (CPG) companies. However, in the last several years, incumbent CPGs have struggled to keep pace with start-ups, which have reinvigorated and reinvented categories ranging from ice cream to diapers.

Our analysis of the food and beverage market from 2013–17 reveals that the top 25 manufacturers are responsible for 59 percent of sales but only 2 percent of category growth. Conversely, 44 percent of category growth has come from the next 400 manufacturers.1 Our experience in working with large consumer companies suggests that they don’t suffer from a lack of ideas; where they struggle is in knowing where to make bets, moving products quickly to launch, and then nurturing them to scale. Effectively driving growth through innovation requires CPG companies to evolve many of the assets and capabilities already in place and adopt significantly different and new ways of working.

This change will not be easy. Many of the innovation systems that need to evolve are deeply entrenched. They have their own brand names, dedicated IT systems, firmly established management routines, and more. However, our work with CPG organizations has convinced us that these changes are necessary and can return significant value. Our analysis of ~350 CPG companies across 21 subcategories found that growth leaders excelled at harnessing commercial capabilities, including innovation. Additional McKinsey analysis has shown that CPG “Creator” companies—those that consistently develop new products or services—grow more than their peers. These winning Creators have adopted a formula that borrows the best from progressive new players while fully leveraging existing advantages in scope and scale.

How did we get here?

For the past two decades, CPG innovation models have been designed to maintain and steadily grow already at-scale brands. This meant that most innovations were largely incremental moves with the occasional one-off disruptive success. This slow and steady approach worked because CPGs didn’t really need disruptive innovation to grow. Geographic expansion, pricing, and brand extensions were all successful strategies that kept the top line moving. As a result, most of the systems designed to manage these innovations were optimized for fairly predictable and low-volatility initiatives. They emphasized reliability and risk management.

That very success, however, led to calcified thinking as companies built large brands and poured resources into supporting and protecting them. In recent years, as they have tried to respond to new entrants and rapidly changing consumer needs, CPGs found their innovation systems tended to stifle and stall more disruptive efforts. As the returns from innovation dwindled, companies cut marketing, insights, and innovation budgets to cover profit shortfalls. This created a negative cycle. As a stopgap, many large consumer companies have turned to M&A to fill holes in the innovation portfolio—but on its own, M&A can be a very expensive path to growth with its own difficulties in scalability and cultural fit.

How new upstarts “do” innovation—speed, agility, consumer-first—is not exactly a secret. Many CPGs have made concerted efforts to embrace those attributes by setting up incubators, garages, or labs. They have tried to become agile and use test-and-learn programs. But while there have been notable successes, they tend to be episodic or fail to scale because they happen at the periphery of the main innovation system, or even as explicit “exemptions” from standard processes. Scaled success requires making disruptive innovation part of the normal course of business.

What to learn from today’s innovators

Despite the many challenges, there are consumer companies winning in the market and driving profitable growth. Here are four shifts they’re making:

1. Focus on targeted consumer needs.

All of us can think of innovative products that are competing head to head in established categories (some of our favorites include Halo Top, SkinnyPop, and Blue Buffalo). A common denominator for most of them is that they didn’t start big but focused instead on a targeted and unmet consumer need that turned out to have broad reach.

That approach stands in stark contrast to the standard CPG model, where companies look for the products that satisfy the largest group (“gen pop”). An important reason for this focus is that many CPGs need an idea to be big enough to make a dent in their business. They also look to get the highest ROI for innovations to amortize the high costs historically required to launch (especially ad campaigns and capital expenditures for new manufacturing). But in a world where it is less expensive and easier than ever for companies to address more targeted needs, and where consumers have never had more choices at their fingertips, gen pop is becoming less and less viable as an objective or requirement.

This isn’t to suggest that large CPG firms should stop looking for large and growing opportunities. But the evidence is clear that there are plenty of products that start small and would normally be killed off at a large CPG company, that explode once in the market.

All strong innovation begins with the ability to identify a consumer need that the marketplace isn’t addressing. That happens by:

- Exploring granular consumer needs with advanced analytics. CPG leaders explore opportunities through highly granular, data-rich maps of product benefits, consumer needs, and usage occasions rather than just segments or categories (we call these Growth Maps). These can reveal how a seemingly niche and emerging trend could have surprisingly broad reach and applicability.

- Combining many data sources to quickly address tipping-point trends. Leaders combine various data sources (consumer, business, technology) to identify market trends that are hitting relevant tipping points. They understand where the most promising trends are, where they have existing capabilities to play, and where they might need to build new muscle. And they bring all this together to rapidly prioritize where to take action.

- Using design thinking. By using empathy to uncover unspoken and unmet needs, designing new solutions with consumers and channel partners, and rapidly prototyping and testing, design thinking produces distinctive answers. Importantly, true design thinking continues to incorporate consumer insights and iterate product designs even after initial product launch (see more below). Two leading consumer companies in Japan recently set up “innovation garages” to integrate design thinking into product development methods. They were excited by the power of integrating design into product development methods to produce better, more consumer-driven products radically faster.

2. Launch more “speedboats”—accepting that some of them will sink.

There is a prevailing myth that consumer companies need to do a few big launches a year. Even if that were once true, it no longer is. This approach required large R&D investments, extensive consumer testing to validate willingness to purchase, and massive resources (large advertising, promotion, and distribution budgets)—all in an attempt to predict success and perfect a product before a large, potentially multicountry launch. This mentality assumed the resulting product could not fail once it hit the open market.

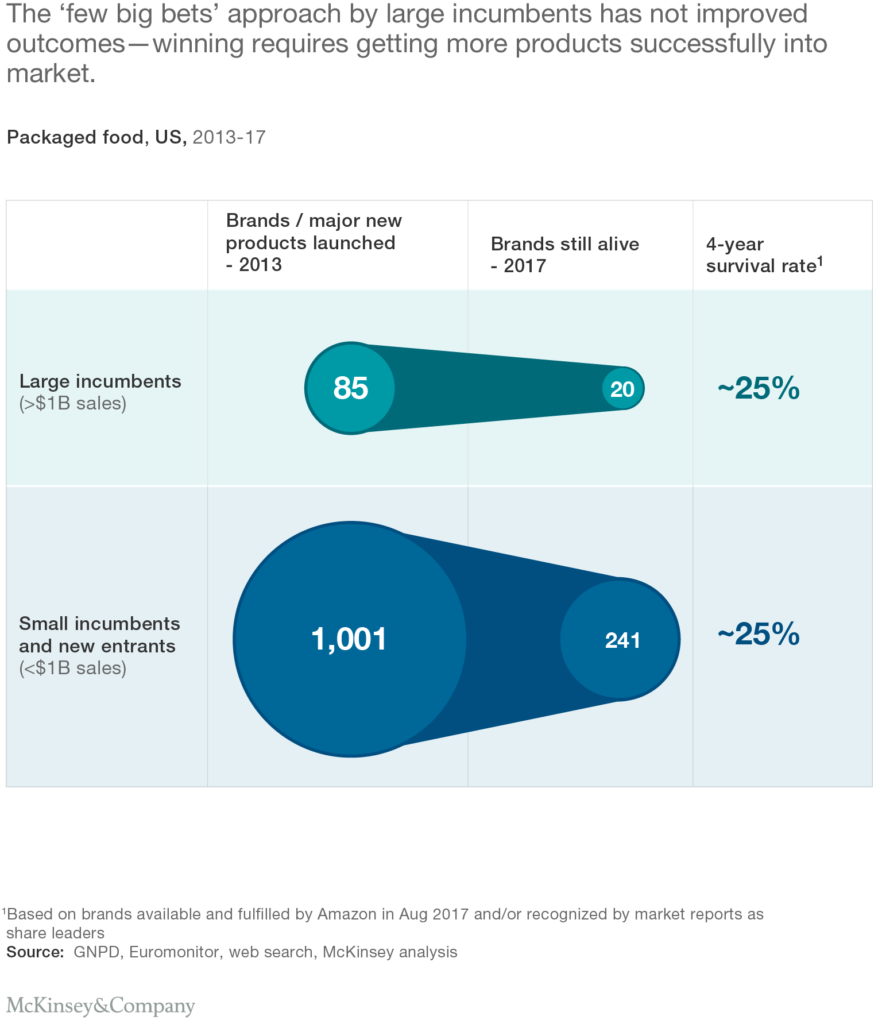

However, our findings suggest that putting all this effort and funding to drive a successful launch has not actually provided the desired results. In packaged food, for example, a review of new brands and disruptive innovations launched in 2013 by large CPG companies found that only 25 percent were still around four years later. This success rate is no better than what start-ups and small CPGs achieved with much smaller budgets and programs.

Winning innovators, in contrast, increasingly rely on speedboats: smaller launches where the product is tested and refined in-market. Take the example of one global CPG that is extensively using “first-purchase testing” to understand why consumers are/are not purchasing a product, then integrating that feedback into further iterations (Exhibit 2). It has been testing real products in multiple nontraditional settings including office buildings, juice shops, and yoga studios. The insights gained from these live settings allow the company to rapidly iterate the product design. Once indicators of success are seen, it moves to rapidly scale the product via Amazon and traditional retailers. The approach works, because in today’s ecosystem, there are many distribution channels and digital and social-media outlets to reach consumers less expensively, as well as external networks that can support efficient and productive discovery and development.

The Internet also provides an under-utilized testing ground for speedboats. Many disruptive brands start by marketing direct to consumers, which allows them to hone the product and messaging, while capturing detailed data on purchase behavior. Even without e-commerce, most start-ups are heavily using social media like Facebook to reach targeted audiences with lower cost and risk.

More speedboats, however, can mean more headaches for general managers who have to keep track of more projects and then nurture products to scale. CPG leaders address this through strong portfolio management. They make clear, prioritized choices about the categories and segments in which they will innovate and which ones they will maintain or exit from. They put in place clear processes for tracking performance and new allocation mechanisms to quickly get funds to promising programs. And when they need to scale new bets, they fund them by reinvesting initial proceeds from the speedboats.

3. Think (and act) like a venture investor.

Traditional stage gate processes are very efficient for managing a large pipeline of similar ideas through a relatively standard development pathway. However, when they are used for more disruptive initiatives, they tend to systematically smother or starve them. A different system is required for disruptive innovation.

Consider how venture-capital firms manage their portfolio of investments. They analyze each investment on its own merits, adapting as businesses evolve. They couple funding closely to the progress of the new business and meet at the speed of its progress versus on a predefined calendar. The hurdle rates and KPIs are also different, with emphasis on whether they are gaining consumer traction in addition to improving financials. And more than anything, they are relentless in pushing the pace and urgency of growth.

To deliver on this capability, we often recommend that companies establish their own venture board comprising their strongest leaders. Even though the scale may be small, this is some of the hardest work in the company and the most important to its future. Along with a few outsiders to inject a more objective perspective, this board is responsible for maximizing the return of the more aggressive portfolio—and has complete autonomy to quickly make decisions about it.

4. First to scale beats first to market.

Launching disruptive innovation doesn’t mean a company always has to be the original inventor. Rather than focusing on first to market, we recommend focusing on first to scale. We found that leading CPG innovators who actively scan the market for high-potential ideas, watch for emerging consumer acceptance and new behaviors, and then jump in before the market landscape has fully evolved have reaped significant rewards. We evaluated 25 high-growth categories in four countries across North and South America, Asia, and Europe. In each, the players who took this approach are winning ~60 to 80 percent of the time; in the US, they win the highest market share 80 percent of the time.

Incumbent CPGs can turn to their ingrained advantages to identify and scale these ideas. Their wealth of consumer data can be used to spot trends earlier than others. Their significant financial and human resources can be disproportionately allocated to hot opportunities. The distribution and account relationships incumbents have across multiple retailers can be used to expand the market for new products more easily and quickly than new players with a smaller network of relationships. Large CPGs are also attractive partners for innovators with insightful ideas but insufficient resources to develop and scale them.

All of the above are incumbents’ advantages that many smaller players would love to acquire. Using these advantages to their fullest requires CPGs to adopt a much stronger orientation toward speed, nurture more disruptive bets until they can be scaled, and reallocate resources to the strongest opportunities.

How to get started

Embracing the above shifts will require meaningful changes. In our experience, the changes are not only eminently achievable, but also reenergize the organization as they make innovation and delighting consumers more central and less cumbersome to accomplish. We recommend CPG leaders do five things now:

1. Address the culture.

Business leaders understand how important culture is but tend to think of it as a vague byproduct of other activities. Building an innovation culture begins with making innovation essential to the day-to-day business, and it’s critical that it start at the top, with the CEO and senior executive team. As one consumer executive—who grew her company to a billion-dollar valuation in less than 15 years—put it, “Innovation is simply everyone’s job. . . . Everyone is expected to look for insights, to bring ideas, to be ready to help drive an initiative.” Other ingredients include: a near-maniacal focus on the consumer—by which we mean putting the consumer at the center of every decision; incentives to reward innovation; metrics that track innovation—consumer excitement, word of mouth, adoption rates; and a clear understanding of how each person’s role adds value to the process. Reward learning and make learnings easily available and easy to share.

2. Create high aspirations and hard metrics.

“Let’s increase growth by 2 to 3 percent!” That kind of aspiration won’t motivate people and drive new thinking. Contrast that rather vague hope with this one from a mining (!) company: “Generate $150 million of incremental EBITDA over the next five years by discovering new applications for our products, moving closer to our end customers, and leading our industry in production processes.” This is bold, actionable, measurable, and gives teams some sense of where and how they should innovate. To track progress against aspirations, metrics need to be specific, of course, but they also need to evolve. For example, metrics on market share or growth rate will be better in the earlier phase of a product’s lifecycle. Shift the focus to value and margin as the project scales and matures. Metrics also must be in the business-unit (BU) leader’s performance objectives.

3. Define the hunting grounds.

Make clear choices about where you will innovate. Be careful to define them by working backward from the consumers and markets you serve rather than the way you currently define your brand and category structures, particularly in multibrand organizations. Too often we see outdated guardrails unnecessarily limit brands from exploring new spaces. As one CEO, whose company was acquired by a leading global CPG incumbent, put it, “If your consumers want your brand to move into a space and you don’t, then rest assured someone else will.”

4. Reallocate resources.

In our experience, most incumbent CPGs have too many resources committed to initiatives that are unlikely to drive meaningful growth. The first step in liberating resources is to take a hard look at the portfolio and reallocate people to more aggressive growth opportunities. Crucially, this cannot be an annual or even quarterly exercise. Leading innovators continually and ruthlessly reallocate resources and make sure scarce people and dollars are put to the best use. As one innovative CPG leader in Asia Pacific said, “I established three simple mandates: bigger (more top-line potential), better (more differentiated), and faster (time to market).” These mandates drove top-line growth at four to five times the underlying category growth.

5. Put a new disruptive innovation “system” in place based on agile models.

Driving success at scale requires a new model. Innovative ideas can initially generate a lot of excitement and promise. But that drive often wilts when it needs to work with the full business to scale the idea. While there is a broad range of elements in a new innovation system, we find that the following are a few of the most important:

- Establish cross-functional teams with a complementary set of problem-solving skills, such as people from insights, marketing, personnel, sales, UX, and tech. The team should “live” together, using an agile development model, and ideally drive one to two initiatives at any given time.

- Focus on constant learning and de-risking throughout development. Rather than a standard checklist of activities and stages, teams should constantly identify and prioritize the greatest uncertainties in a concept and conduct quick tests to resolve them.

- Set up and prequalify your “speedboat” network. These can be factories, partners, agencies, and vendors who can support small-scale procurement and manufacturing, run first-purchase tests, and even support a riskier new product’s first few years of manufacturing before committing the capital expenditure for scaled/global manufacturing.

- Hardwire points of contact between the innovation labs and the “mother ship.” Embed people from the sponsor BU as a core part of the innovation team, and rotate people from the main business through the innovation labs. Assign respected leaders from the legacy business to manage innovation projects. Create a central innovation roadmap that business units agree on, and track it on the CEO/COO agenda.

The growth game has changed, but that doesn’t mean that CPG companies can’t change with it. With a commitment to new mind-sets and approaches, CPG companies can harness speed and agility to move again to the forefront of innovation.

About the author(s)

Mark Dziersk is the LUNAR Industrial Design Leader in McKinsey’s Chicago office, where Brian Quinn is a partner; Stacey Haas is a partner in the Detroit office, and Jon McClain is an associate partner in the Washington, DC, office.

The authors would like to thank Marla Capozzi, Max Magni, Audrey Manacek, Erik Roth, and Jeff Salazar for their contributions to this article.